The Camel vs. The Wheel in Creating Wealth in the Islamic Empire

In This Article

-

The camel emerged as a superior economic engine in regions where the wheel struggled against harsh terrain.

-

Trade networks expanded not merely through innovation but through the intelligent adaptation of technology to environment.

-

The story of the camel and the wheel reveals how civilizations build prosperity by aligning their tools with their geography.

Traditional wisdom holds the wheel to be one of mankind’s cleverest inventions and the camel to be one of God’s clumsiest (Richard W. Bulliet, The Camel and the Wheel, NY: Columbia University Press, 1990, 7). Yet this is the creature that has affected history as much as the horse: the horse was fundamentally the servant of the warrior, the camel of the merchant (James Wellard, Samarkand and Beyond: A History of Desert Caravans. London: Constable, 1997, 30).

Wheeled vehicles and ships were known in the Middle East since before Roman times. They served different segments of the “transportation industry.” Ships could carry the heavy loads that animal transportation could not. However, the camel was used more than a ship and replaced the wheel as a matter of practicality. The wheel’s associated vocabulary had disappeared sometime prior to the seventh century Islamic conquests in the region. For example, it has been noted that records of the Crusades in the Middle East never mention carts and wagons (Bulliet, The Camel and the Wheel, 9).

Camel caravans are slow. The fully loaded pack camel can, at the limit, march only for thirty miles a day for three or four days without watering (Wellard, Samarkand and Beyond, 31) A caravan, however, could travel difficult routes and get to its destination where a ship, a wheeled cart, or a wagon could not. Between 300 and 1300 CE, the caravans carried goods more cheaply, more quickly, and with less seasonal interruption than any other form of transportation (William H. McNeill, “The Eccentricity of Wheels, or Eurasian Transportation in Historical Perspective” in The American Historical Review, Vol. 92, 1987).

Perhaps because Muhammad was a merchant camel driver before he became the Prophet, trade has always been valued in the Islamic world. This paper argues that even though there was marine activity, the camel became the prime means of transportation in the Middle East and surrounding areas, ultimately resulting in distribution of wealth in the early and medieval Islamic Empire. The preference for the camel over the wheel is a good example of technology not always triumphing over nature.

As mentioned earlier, the Middle East had transportation other than on the land: Arabs were wonderful seafarers. They sailed the Mediterranean since the beginning of Islam. They also sailed the Indian Ocean and made contact with India and China. Articles of Indian manufacturer are found in Babylonia (George F. Hourani, Arab Seafaring in the Indian Ocean and in Ancient and Early Medieval Times, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951).

Despite this, the Arabs have always been traditionally skeptical about seafaring. Even the fearless general Amr ibn Al-As, who conquered Palestine and Egypt in 640 CE said: “There is little trust and great fear. Man at sea is like an insect on a splinter of wood – always in danger of being swallowed up by the waves and always frightened to death.” On rivers, however, there were no such misgivings. The Nile, for instance, has been used for traffic from time immemorial (Walter M. Weiss, Kurt-Michael Westermann, E.T. Balic, Lorna Dale, The Bazaar: Markets and Merchants of the Islamic World. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1998, 30).

But there were also practical reasons for ships not being the dominant form of transportation, not the least the geography of their homeland. The Arabian Peninsula has no navigable rivers or natural harbors, and the hinterland is not populated. The razor-sharp coral reefs along its coasts are hazardous to shipping. Nor does it have any of the raw materials necessary for shipbuilding: wood or resin or flax for canvas sails. Another reason was the technology. The Arabs had introduced the triangular “Latin” sail to the Mediterranean and invented the stern rudder, but unlike the Europeans and Chinese, they joined their ships’ planks together with ropes made of coconut fiber and not with nails (there was a legend that a magnetic mountain under the sea draws nails out of the wood). This made them much less durable, especially if there was a storm at sea (Weiss et al. The Bazaar, 31).

One reason ships were never truly competitive with the camel was piracy. In sailing down from the Persian Gulf, one had to be aware of pirates (and also of various reefs in the sea) from al-Bahrayn, Qatar, and the Iranian coast. The pirates raided widely over the Indian Ocean, even occasionally as far as the mouth of the Tigris, the southern part of the Red Sea, and the costs of Ceylon. For defense against them, merchant ships had to carry marines trained to throw Greek fire, a combustible compound emitted by a flame-throwing weapon and used to set light to enemy ships. It ignited on contact with water and was probably based on naphtha and quicklime (Hourani, Arab Seafaring, 69). Another reason ships were outdone by the camel was that camels could travel inland to places where ships could not go.

Camels can go a week without water and a month without food. A thirsty camel can drink 25 to 30 gallons of water at one go. For protection against sandstorms, Bactrian camels have two sets of eyelids and eyelashes. The extra eyelids can wipe sand like windshield wipers. Their nostrils can shrink to a narrow slit to keep out blowing sand. Long-distance transport was what camels excelled in, plodding day after day cross-country, almost regardless of the quality of grazing available to them along the way (McNeill, “The Eccentricity of Wheels,” 1987). The camel is thus the animal par excellence of the open desert (Carlton S. Coon, Caravan: The Story of the Middle East, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1958, 191).

Weighing more than 1,500 pounds, adult camels can reach a height of 6 feet at their shoulders and 7 feet at their humps. Camels have two hoofed toes on each foot, under which a leathery pad links the two toes. When camels walk, they spread their toes as wide apart as possible to prevent their feet from sinking into the sand. The tough, leathery pads under their feet also allow camels to walk on stony, rough ground. Camels are nicknamed (ironically, considering that sailing was a viable form of transportation) "ships of the desert" because mimics the side-to-side roll of a boat: they move both feet on one side of their bodies, then both feet on the other.

Evidence shows that the camel became domesticated in the Middle East around the late Bronze Age (1200 BCE). Camels replaced wheeled vehicles apparently after the third and before the seventh century CE (Bulliet, The Camel and the Wheel, 16). The camel's great virtues include the ability to carry substantial loads--400-500 pounds--and their well-known capacity for surviving in arid conditions. The question is: why did the camel (one-humped) replace the wheeled vehicle as a standard means of transportation throughout virtually the entire range from Morocco to Afghanistan? (Bulliet, The Camel and the Wheel, 8). The use of the camel as the dominant means of transporting goods over much of Inner Asia is in part a matter of economic efficiency--as Richard Bulliet has argued, camels are cost-efficient compared with the use of carts requiring the maintenance of roads.

In the desert sands, the Arabs were indisputably masters. Long before the emergence of Islam, the Bedouin, traveling to grazing grounds at night, had become familiar with the constellations and could identify more than 250 stars. The Arabs had begun to use camels rather than carts for transportation. Camels were more useful because they adapted to any terrain and were better able to cross obstacles such as fords or passes, making surfaced roads like those built by the Persians and Romans superfluous (Weiss et al., The Bazaar, 8). The economic and cultural geography of Africa and, to a lesser degree, of central Asia was profoundly altered when camel caravans made the deserts penetrable. The realm of Islam became capable of spanning barren deserts in the same way that European civilization later became capable of spanning vast oceans (McNeill, “The Eccentricity of Wheels”, 1116). In the early days, the land-routes were used much more than sea-routes, which was neither favored nor trusted and was used only when absolutely necessary. Transport by camels across the desert was reckoned a far safer and more trustworthy method of conveyance than that by ship, and it was mostly by means of caravans that the products of India, Arabia, and even central Africa were dispatched from Arabia to Babylonia, to Syria, to Egypt, or even much farther to north and to west (M. Rostovtzeff, Rostovtzeff, Caravan Cities. Translated by D. Rice, and T. Talbot. Oxford: The Clarendon Press. 1932, 3).

The western route, which brought spices of India and the incense of Hadramawt to the high-storied cities of Yemen, passed through ‘Asir and the Hijaz. Mecca was one stop, Medina another. Higher up, the route forked the west branch leading to the Mediterranean, the east to the Damascus, Homes-Hama-Aleppo string of cities. During this period, the influence of south Arabia was dominant in the rest of the peninsula (Coon, Caravan, 62).

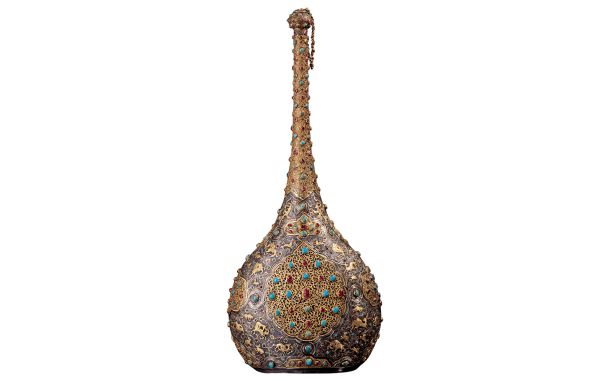

The bazaar, a market in a Middle Eastern country, is a unique achievement of Islamic culture, but the fundamental impulse that inspired it--to trade and barter for profit--is, of course, as old as the human race. Caravans created wealth for the cities and stops along their travels. In the bigger towns, the larger caravans stayed for a while, resting and fattening up their animals, purchasing new animals, relaxing, and selling or trading goods. To meet their needs were banks, exchange houses, trading firms, markets, brothels, and places where one could smoke hashish and opium. Some of these caravan stops, such as Samarkand and Bukhara (cities in modern Uzbekistan) became rich cities (Wellard, Samarkand, 81).

With camel trade, as the Ottomans conquered important parts of Asia Minor, the Karimis (Muslim merchant traders) expanded their trading activities into this area. In Africa, they traded not only on the west coast of the Red Sea, but also on the caravan routes with Nubia and Ethiopia. Their trading activities reached into distant Ghana and Mali, where from the most important gold mines in the world they obtained gold (Subhi Y. Labib, “Capitalism in Medieval Islam” in The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 29, No. 1, The Tasks of Economic History, 82). Steady traffic and the relative safety of the roads contributed considerably to the growth of trade (Labib, “Capitalism,” 35).

Intimate symbiosis between urban and nomadic elements in Middle Eastern society was, in fact, an essential substructure for smooth operation of the caravan transport network. A caravan was seldom far away from populated places, and caravans concentrated wealth in a way that tempted innumerable plunderers (McNeill, “The Eccentricity,” 1119).

Between towns and oases people on long caravans often slept in yurts or under the stars. However, the rest houses and stores that Cyrus the Great (600-530 BC) built along the long-distance route, which we now call by the later Turkish name caravanserais, were far from superfluous. In fact, their numbers increased as trade developed. A caravanserai was a roadside inn where travelers (caravaners) could rest and recover from the day's journey. As stopping places for caravans, caravanserais offered lodging, stables, and food. They were not all that different from guesthouses used by backpackers today except that people were allowed to stay for free. Owners made their money from charging fees for animals and selling meals and supplies. Caravanserais supported the flow of commerce, information and people across the network of trade routes covering Asia, North Africa and Southeast Europe, especially along the Silk Road. The towns that housed them also prospered (Weiss et al., “The Bazaar,” 58).

The cradle of Islamic capitalism was in the main of the Islamic world. In the early Middle Ages, Baghdad was the commercial metropolis and exerted a marked influence over the whole of Islamic big business. As mentioned earlier, commercial ship navigation also contributed to Baghdad’s wealth. The Euphrates was connected with the Tigris by several navigable canals, of which Nahir ‘Isa terminated at Baghdad (Hourani, Arab Seafaring, 64).

With the tenth century, however, the weight of Islamic commerce was gradually shifted to sailing from Iraq and the Persian Gulf to Egypt, the Red Sea, and the harbor of the Arabian Peninsula on the Indian Ocean. Cairo became the leading city (Labib, “Capitalism,” 81).

Thus, maritime activities contributed to local wealth, but not as much as camel caravans. For example, Siraf, on the coast of Iran, south of Shiraz, like Aden in Arabia was hot and barren and lived on supplies brought by sea; its existence was due entirely to its sea commerce (Hourani, Arab Seafaring, 69). Camels were unable to carry extremely heavy loads such as logs and large grain shipments, and merchants had to rely on ships for this type of transportation. Typical merchandise carried by camels was commodities such as wool, cotton fabrics, tea, spices, myrrh, incense, and occasionally opium.

Mecca was the last of the great caravan cities. It probably began as a tribal shrine, with perhaps a surrounding encampment. Mecca produced nothing; it consumed only negligible quantities of the incense and spices that were a staple of the trade; and there was no natural resource such as a river to require transshipment (Bulliet, The Camel and the Wheel, 105). The main caravans, one in the summer and one in the winter, were communal undertakings in which all the tribes took part. Mecca and Medina were not only the holy places of Islam, but also the cradle of its culture, its business, and its government (Labib, “Capitalism,” 79).

Innovation and keeping up with new developments are part of human nature. Although the obsession with technology might be considered “modern,” it is not really. The ancients invented many things such as the stirrup, ships, and Greek flame throwers, and undoubtedly took pride in being up-to-date and to use a twentieth century word “competitive” with the latest technology.

On the other hand, the reversion of the Middle East to the “technology” of the camel as a prime means of transport instead of the seemingly more advanced wheeled carts was an anomaly, driven, as has been shown, by practicality and cost. It can be argued that the geography of the area was also a consideration, as it impacts distance and accessibility, commonly the most basic considerations affecting transportation costs.

But things change with time. The trans-Saharan caravans of up to 24,000 camels, covering distances of several thousand kilometers, finally seemed to come to an end at the beginning of the 20th century. There were many reasons, all connected with the growing influence of the European powers in the north and west (Weiss et al., The Bazaar, 31). The system was seriously endangered by the catastrophic drought there in the late 1960s and when rainfall was at a record low in the beginning of the 1980s, salt caravans were stopped the government replaced them with trucks. An age-old tradition had finally died out or so it seemed. But in 1986, the old mode of transport was revived, as though it had been brought to a temporary halt by the climate. Once again, the camel had triumphed (Weiss et al., The Bazaar, 31). That camels lasted as long as they did is a testament to the belief that what is “modern” and “technological” is not always the best.

References

https://www.edhelper.com/AnimalReadingComprehension_25_1.html).